Art by Emmalynn González | Todas and Centro de Periodismo Investigativo

She had wanted to become a mother her entire life. María González, whose name was changed to protect her identity, longed to raise a child as part of a couple and in a stable environment. When that opportunity came up, around the age of 39, her egg count was very low.

“I was very sad… The chances of having a baby were very, very low,” González recalled about her first impression upon receiving the results of the anti-Müllerian hormone blood test, aimed at assessing her ovarian reserve.

Even with those results, her gynecologist recommended she continue to try to get pregnant with her partner for six more months. However, she –following a friend’s recommendation– decided to go to one of the five assisted reproduction specialists in Puerto Rico, where she discovered that one of her fallopian tubes was atrophied and that she suffered from endometriosis.

The woman, a planner by profession and a resident of San Juan, underwent tubal surgery and in vitro fertilization that did not result in pregnancy. Except for a few labs that her health plan covered, she had to pay for every one of her procedures, for which she borrowed $10,000 from her sister.

The experience that González shared in an interview with the Gender Investigative Unit –an alliance between media outlet Todas and the Centro de Periodismo Investigativo (CPI)– represents some of the challenges faced by those seeking assisted reproduction treatments in Puerto Rico. Most health insurance plans do not cover these procedures, even though they are closely linked to diagnoses of infertility, a disease of the reproductive system that prevents pregnancy, according to the World Health Organization.

Conditions such as endometriosis are also treated with interventions like those used to treat infertility, even if the goal is not to conceive. The financial cost is added to the emotional impact of frustrations and grief over unsuccessful pregnancies and the social stigma associated with infertility and assisted reproduction treatments.

“When you think you have to invest $10,000 to try (to get pregnant) without any guarantee, the process is too emotionally painful and hurts your pocket. And it competes with other things… what will you raise the child with? What are you going to start your life with? Having a child is expensive,” González said about the economic and emotional difficulties that assisted reproduction currently entails.

In 22 states in the U.S., health insurance plans offer some type of infertility-related coverage, according to data from the American infertility association Resolve. Although requirements vary by state, Utah, Colorado, Illinois, New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Delaware, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Maryland offer some type of coverage for fertility preservation, in vitro fertilization, or both.

At a time when birth rates have reached their lowest point in Puerto Rico’s history, some of the women who want to become pregnant feel that the government could do more to help them.

Assisted reproduction consists of any treatment aimed at achieving pregnancy, according to the National Institutes of Health (NIH). These procedures include intrauterine insemination, in vitro fertilization, sperm donation, egg donation, surrogacy, and embryo donation, among others.

The World Health Organization estimated in a report published in 2023 that, worldwide, one in six people has infertility problems, and that assisted reproduction procedures remain inaccessible due to cost, shortage of clinics and specialists, and the stigma associated with treatment.

The three people interviewed by the Gender Investigative Unit agreed that in vitro fertilization treatment can cost between $10,000 and $18,000, depending on the medications needed and whether eggs or sperm are being purchased.

“There’s Also an Element of Discrimination for Women”

For Dr. Rosa Cruz Burgos, head of the Gynecology Reproductive Endocrinology Fertility Institute clinic, infertility is usually the consequence of an underlying condition. So, the costs of fertility treatments affect not only those who want to have children, but also those who have conditions that require fertility treatment, even if they do not want to have children. According to the gynecologist, conditions such as endometriosis and uterine fibroids can be treated with fertility-related procedures. As a result, these patients also suffer from the lack of health insurance coverage for their treatments, even if their intention is not to have children.

“Infertility is the consequence of something, and that something can be a medical condition of the reproductive system such as endometriosis, uterine fibroids, polycystic ovary problems… You cannot deny endometriosis treatment to a patient because, if treated, they’re going to get pregnant,” argued Cruz Burgos, who is the only woman who runs a fertility clinic in Puerto Rico.

The obstetrician-gynecologist also pointed out the discrimination by health insurance companies based on gender in fertility issues. She recalled that she recently prescribed the same infertility medication to a couple with the same health insurance plan. She had ovulation problems, and her partner had an altered semen analysis, a situation in which the results of the semen analysis deviate from the normal parameters established by the laboratory that processes the sample. “I give the medication prescription for 30 days to her husband and I give the same medication to her for five days. The health insurance plan covered his, but it did not cover hers,” Cruz Burgos recalled. “There’s also an element of discrimination for women there,” she continued.

Besides Dr. Cruz, the assisted reproduction specialists in Puerto Rico are doctors Nabal Bracero, Pedro Beauchamp, Amaury J. Llorens, and José R. Cruz Díaz. On May 30, 2024, Dr. Beauchamp announced his retirement after 39 years.

The Gender Investigative Unit contacted the local health insurance companies Triple-S, MCS, First Medical, Plan de Salud Menonita and the Auxilio Mutuo to find out if their coverage includes infertility treatments.

Triple-S responded that it covers infertility treatments only for federal employees per the requirement of the U.S. Office of Personnel Management. Meanwhile, Auxilio Mutuo said they don’t cover fertility treatments in their member’s plans. At the time of this story’s publication, MCS, First Medical, and Plan de Salud Menonita had not responded about their coverage.

A Triple-S representative stated in an email that federal coverage is processed through reimbursement. “The plan for these federal employees covers infertility services up to a maximum of $10,000 per member, through reimbursement, because no contracted providers cover these benefits. Additionally, some commercial clients or self-insured employers, in which Triple-S manages their services and benefits, request this infertility coverage as an additional benefit.”

She said the treatments are subject to preauthorization and cover a maximum of three cycles per year “for members with female reproductive organs aged 35 years or older.” In vitro fertilization is also included among assisted reproduction services. In the case of people with a male reproductive organ, the treatments “are mostly pharmacological and laboratory analyses that are included” in the basic coverage for federal employees of the commercial business.

Among the services included in the Triple-S coverage for federal employees are artificial insemination, intravaginal insemination, intracervical insemination and intrauterine insemination. Covered medications are clomiPHENE Citrate, Chorionic Gonadotropin, Follistim AQ, Ganirelix Acetate, Menopur, Novarel, Ovidrel and Pregnyl.

An attorney who did not want to be identified estimated that the cost of her infertility treatment exceeded $40,000 after undergoing three in vitro fertilizations and two intrauterine inseminations that did not result in a pregnancy. For her, treatments depend almost exclusively on economic factors.

“Access to assisted reproduction treatments is so difficult in terms of cost that people who get to where I am [having tried in vitro fertilization] are much fewer than I’m sure could benefit,” she explained. She said she would have continued with the treatments if it were not for the cost.

“The Emotional Toll is High Too”

Idaliz Rodríguez, a pharmacist from the San Juan area, longed to have the same friendly relationship with her children that she has with her mother. When she turned 38, her ovarian reserve was very low and, after intrauterine insemination and three in vitro fertilizations, she gave up trying.

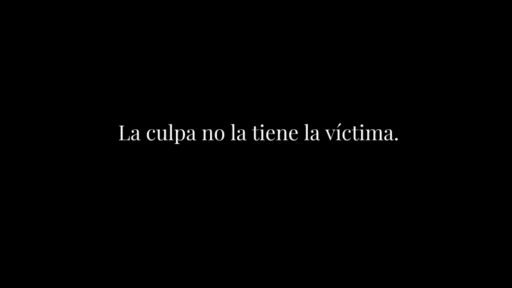

For her, the most painful thing about the process was the emotional toll that the procedure took. “With each cycle, it’s more difficult to overcome it… I went into what I could classify as depression, in a very deep process of mourning and loss… It isn’t only the loss of two embryos, but also the loss of that life that I always imagined. The truth is, I always imagined that I was going to be a mother,” she said. “The emotional toll is high too.”

The lawyer, who did not want to be identified, also explained that, aside from how invasive the in vitro fertilization processes usually are on the bodies, one of the most difficult parts was dealing with the feeling of loss. “This process is a roller coaster… How do you recognize grief when there wasn’t even a pregnancy?” she said about her feelings while undergoing treatments, during which she constantly received positive and discouraging news.

Meanwhile, María González described her process as a disappointment. “I don’t see it as a loss of a pregnancy, but as a loss of hope, of expectations, but I never felt pregnant… Maybe it was me protecting myself because I knew my chances were very low,” she recalled about her experience.

According to perinatal psychologist, Zilkia Rivera Orraca, even if there was no pregnancy, the feeling of loss is common and valid.

“There’s always a sense of loss. There doesn’t have to be a real, concrete, physical loss for the sense of loss to exist,” the psychologist said.

Rivera Orraca said when assisted reproduction processes do not work, people often experience sadness, disappointment, frustration, and anger, among other emotions.

“They’re very strong sensations… and they involve a lot of self-concept; that image that this woman had of herself, of her healthy body, of her body and her well-being, suddenly everything is disrupted when she cannot achieve that pregnancy that she wants,” she said.

She noted that although not everyone needs to seek help and that, for some people, assisted reproduction processes are quick and successful, she recommended pairing these treatments with a mental health professional.

The specialist also alluded to the stigma and individual difficulties in terms of mental health that many women and men who undergo fertility treatments experience. These include imposed social expectations in which couples must try for children when they are stable, pressures from the biological clock and questions of male virility and manhood, as well as internal psychological processes in which people grapple with the dream of starting a family and what it means to fall short of that.

“There’s a lot of complexity in the process. It’s painful and there are psychological manifestations that can be more acute, on one side and the other, for both men and women,” Rivera Orraca said.

Faced with these complexities, she urged the general population to be empathic with these persons by acknowledging their processes, avoiding being invasive and asking too much about aspects they don’t want to talk about, and having a lot of understanding with their experiences. “These issues have a real impact. We cannot continue to see this as something merely biological,” she stressed.

The Importance of Sexual and Reproductive Education

María González emphasized the importance of making informed decisions.

“I don’t feel that I had any indicators in my life that made me think that I could have reproductive challenges,” she said, after explaining that her menstruations were bearable in terms of pain and with cycles that she could easily predict, compared to some of her friends.

She said she would have liked to know, much earlier in her life, that the test to measure ovarian reserve existed. “No one ever told me we’re going to do this test on you,” she recalled. She also said she would have liked to know more about the egg-freezing processes when she was younger.

González believes that more people would opt for assisted fertility procedures if health insurance plans covered them. “Many people would try it if they knew they had that support,” she said.

Meanwhile, Idaliz Rodríguez said sexual education usually focuses on how to avoid pregnancy, but that it should be more comprehensive and include how to preserve fertility. “Maybe I had the [financial] means in my thirties to preserve my eggs, which were going to be of better quality than my eggs at the end of my 30s, but no one told me that I could do that,” she said.

Rodríguez, who created the “Living with Infertility“ website to support other people who are going through the same process, said she would change many aspects of sexual education, including giving visibility to the fact that not everyone can have children. “[You must] change that mentality of ‘when you have children’ and recognize that motherhood and fatherhood are optional, and sometimes, it isn’t even by choice, but rather by what destiny has in store for you,” she said.

Idaliz Rodríguez

She added that there is not enough support for people who want to give birth at an early age, that motherhood must stop being romanticized, and that each person’s processes must be validated. “There is a lot of education to be done… Generally speaking, saying things like ‘don’t give up’ or ‘have faith’ calls into question the effort one is making.” She said the most important thing is to listen and practice empathy.

Rodríguez added that the narratives regarding the historic low birth rates in Puerto Rico at present time minimize the people who have not been able to conceive. “Also, we infertile people contribute significantly to society, we pay higher tax rates, we don’t have deductions… and those things aren’t valued or reciprocated in terms of benefits to us,” she argued.

Bill that Proposed a Change Fails to Pass

The House of Representatives shot down Senate Bill 941, by Sens. Ana Irma Rivera Lassén and Rafael Bernabe, (both from Citizens Victory Movement party, MVC), which, given the high costs of assisted reproduction processes and the historic low birth rates, sought for medical insurance plans to cover these treatments, regardless of the person’s gender. Independent Sen. José Vargas Vidot and New Progressive Party Sen. Nitza Morán were co-authors of the measure.

“(It’s) a big disappointment because we worked hard to get this bill ready for discussion, but unfortunately the Health Commission did not give it the importance or priority necessary for the bill to be discussed,” said Rivera Lassén.

The senator said the bill responded to Puerto Rico’s demographic crisis.

“There’s a lot of talk about the demographic crisis [but] they look the other way about an important component of the demographic issue, which is giving the possibility to people in Puerto Rico who want to have children… We must bring attention to that and the high cost that this represents,” said the now candidate for Resident Commissioner in Washington D.C. for the MVC.

PS 941 was approved in the Senate on April 29, 2024, with 18 votes in favor and five against. On May 7, it was referred to the House of Representatives’ Health Committee, but according to data from the Office of Legislative Services, no public or executive hearing was held there.

Rivera Lassén said many people were waiting for the bill’s approval to benefit from it and called her office “all the time” asking about its status.

Because June 25 was the last day to approve measures and this one did not move forward, Rivera Lassén promised that it would be resubmitted next term.

“As soon as those elected by the people of Puerto Rico are sworn in, we hope that (PS 941) will be submitted again. The MVC’s commitment is that we will submit it again to complete the process, and we hope that everyone supports it,” she said.

Meanwhile, the interim executive director of the Health Insurances Administration (ASES, in Spanish), Roxanna Rosario Serrano, said in a letter dated October 3, 2023, before the public hearing, that they do not oppose the approval of PS 941 if Plan Vital (the public health insurance plan) is provided with funds to cover the proposal’s fiscal impact. She also said the bill, as proposed, represents “great challenges” for ASES.

“Every health service, whether private or public, entails a series of costs and expenses, not only at the time of implementation, but in the process before it… [As for PS 941], we don’t oppose its approval if the specific parameters are established, as well as the designation of funds necessary to cover the budgetary impact that such changes will entail in the government of Puerto Rico’s health insurance plan,” she said.

Although 22 states have laws in favor of medical insurance plans covering assisted reproduction, in the United States, conservative movements have promoted measures that seek to grant legal personality to fetuses, that is, that fetuses are considered people with rights. These bills could impact the right to abortion, but also the use of in vitro fertilization.

Similarly, fertility procedures recently made headlines at stateside news outlets after Baptist churches voted, on June 12, for the first time, to oppose the destruction of embryos not used in in vitro fertilization processes. In May, the Baptist Church’s public policy chief sent a letter to the U.S. Senate calling for action against in vitro fertilization over moral concerns.

Meanwhile, hundreds of women in Puerto Rico continue to pay the high costs –financial, physical, and emotional– of infertility.