When Yarelis Ortiz Rivera found out she was pregnant at 23 years of age, she contacted nearly 15 gynecologists. Not one was able to see her. “It was very, very complicated. Very uphill,” she reminisced from her home in Bayamón. She remembered how some were not obstetricians, others had appointments too far out, were not admitting new patients or were not accepting her health insurance.

Through a friend, her mother found the doctor who was able to see her during that time. But the challenges did not end there.

She faced a legal process with her partner that led to their rupture, she lost friendships, and suffered postpartum depression. Within a year and three months of giving birth, the birth rates in the country dropped to historic levels, but Ortiz Rivera assures that her financial and emotional situation in addition to the country’s social and economic situations make it impossible for her to have another child.

“I can understand the situation that we had last year, a decline as it relates to births here in Puerto Rico, the most extreme in our demographic history. I can understand it, but one also must understand reality and the situation that Puerto Rico is suffering,” she manifested to then later insist on her own reality: “Ideally, I would have another child. Realistically, I cannot have another child.”

When thinking of a new pregnancy, Ortiz Rivera acknowledges that the emotional and financial complications transcend any longing that she may have to have another child, for the moment.

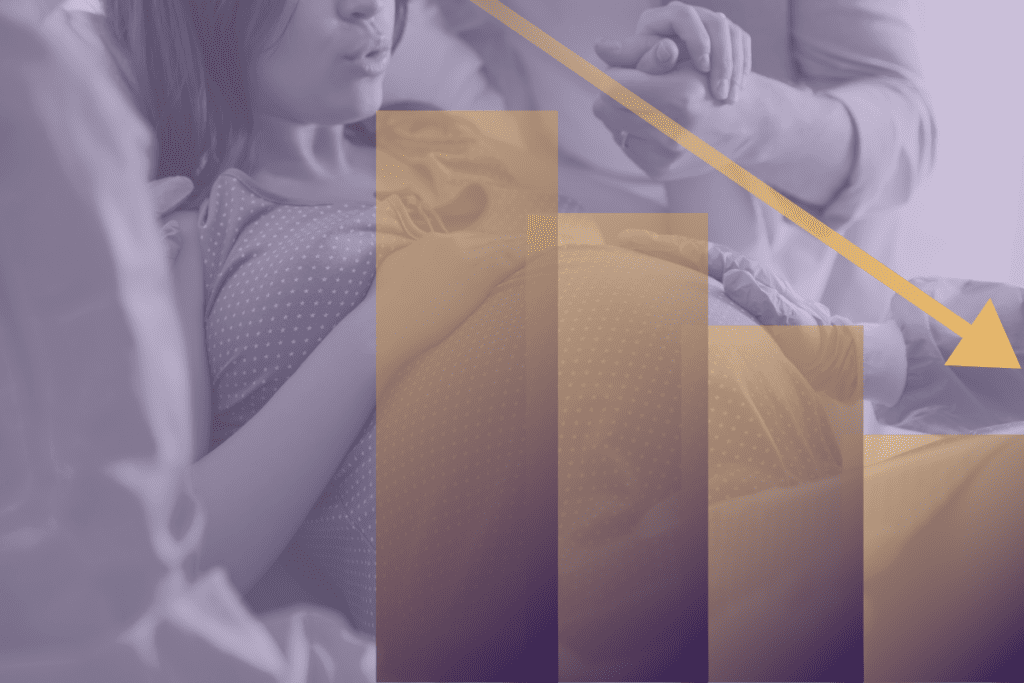

Preliminary data from 2023 shows that the number of births in Puerto Rico reached its lowest point since there is a registry in the country. In fact, Health Secretary, Carlos Mellado López, warned last year that the drop in birth rates is “a serious problem” and attributed responsibility to women for this decline.

At that time, Mellado López offered, as a measure to incentivize women, the existing funds for the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC).

Now that more than 10 delivery rooms have closed in the last decade in Puerto Rico, there has been a surge in promoting an increase in birth rates by way of credits and tax exemptions, such as a measure presented by representative José Bernardo Márquez Reyes from the Citizens’ Victory Movement. This initiative remains under revision in the Puerto Rico House of Representatives and proposes a credit of $1,200 per dependent, $1,000 for student loan payments, and tax deductions for housing rent and moving to Puerto Rico, among others.

In turn, the government announced, for the third consecutive year, a credit for underage dependents that would allow their guardians to receive up to $1,600 per minor.

Nevertheless, according to demographer Melissa López Rosa, an increase in birth rates is not expected in the years to come.

“An increase [in natality] is not expected unless… some changes occur,” explained López Rosa. According to the also professor, the decrease in population in the country requires public policy that improves the conditions for mothering in the country.

Likewise, she assured that the natality issue supposes several challenges for the country among which they are: a greater number of older adults and a smaller population of younger people, fewer contributions to the retirement systems, and more older adults without caregivers.

Continuous control over pregnant bodies

Historically, control over natality has weighed on Puerto Rican women. That is how economist and planner Martha Quiñones Domínguez remembered it when alluding to the racist and forced sterilization that many women suffered in the mid 20th century and the experiments with birth control pills that took place in the country.

“It is a historical matter that is not answered simply by saying that women do not want to give birth. It is answered because that is the discourse that society built [in which] … women were also discriminated against if they had children,” explained Quiñones Domínguez.

Now, when the discourse was modified to increase birth rates, the living conditions in the country are not designed to sustain motherhood. “Having to work for a minimum wage and find money to sustain a family is much more difficult,” emphasized the also professor at the University of Puerto Rico in Arecibo.

In turn, she also mentioned that the lack of access to housing, day care centers, and pediatric and gynecologic services further complicate the possibility of mothering.

In December of 2023, the Puerto Rico Institute of Statistics and the Women’s Advocate Office revealed the results of a survey where over 13 thousand women participated. In the study, 47% of the women indicated that their workplace does not have a nursing room and 67% mentioned that the room provided by their employer was not adequate. Additionally, one in three women expressed the need for a caregiver for their children.

When observing the economic, political, and social conditions of the country, Elba Betancourt Diaz, a professor and social worker that decided not to have children, remains firm in her decision. Moreover, she urges the government to not blame women for birth rates and in its place, improve the living conditions for those who wish to mother.

“They cannot blame us women because there are many other factors that influence our decision to have or not to have children and, for example, starting with public policies we need to have and create an environment in which we can, whoever chooses to, mother. But mothering in a supportive, safe, protected environment, with the least amount of worry possible, knowing or having the certainty that there is someone or that, at least, public policy accompanies you in those processes,” manifested Betancourt Díaz.

Public policies in favor of motherhood

Economist Quiñones Domínguez mentioned that a favorable space to mother begins with changing the logistics so that working people can pick up their child’s grades from school outside of working hours. Equally, promoting extracurricular activities that allow children to stay until a later time in a school environment to make way for their families to pick them up after work.

Other favorable policies to increase birth rate, according to the professor, are to provide day care centers that are near and safe, maintain schools near rural areas, improve access to health care, recognize the caregiver’s role as a job, and provide accessible nursing rooms with the appropriate refrigeration.

A study in 2019, promoted by the United Nations Population Fund, found that birth rates are sustained most effectively when public policies that include regulations in the job market, gender equality and educational processes are implemented.

In turn, the report revealed that public policies should go beyond promoting funds for pregnant people. According to the report, the efficiency of policies improves when they are stable, meaning, that they do not change over time; and when people are informed so that they can make decisions over their reproductive rights.

In the meantime, Yarelis Ortiz Rivera does not trust that a subsidy on behalf of the Puerto Rico government will be enough to convince her to pursue motherhood again.

Yet she maintains her focus on healing, accompanied by mental health professionals, the challenges that arose before, during, and after giving birth.

“I have had to be hand in hand with my psychologist during this process of support, of healing, of giving an end to life before motherhood and starting to adopt this process of motherhood,” she mentioned.

Ortiz Rivera also expressed that her process would have been much more manageable had there existed more support resources for women at an informative level that would explain financial planning, what postpartum depression consists of, the changes in routine, and the physical, financial, and emotional changes that come with becoming a mother.